Lumbar disc herniation occurs when the gel-like core of an intervertebral disc pushes through its outer layer, often causing back pain, sciatica, or nerve-related symptoms. It most commonly affects adults aged 30–50, particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels, which bear the most stress. Men are twice as likely to experience this condition as women. While most cases resolve within 6–12 weeks of non-surgical care, severe symptoms like cauda equina syndrome require urgent medical attention.

Key Points:

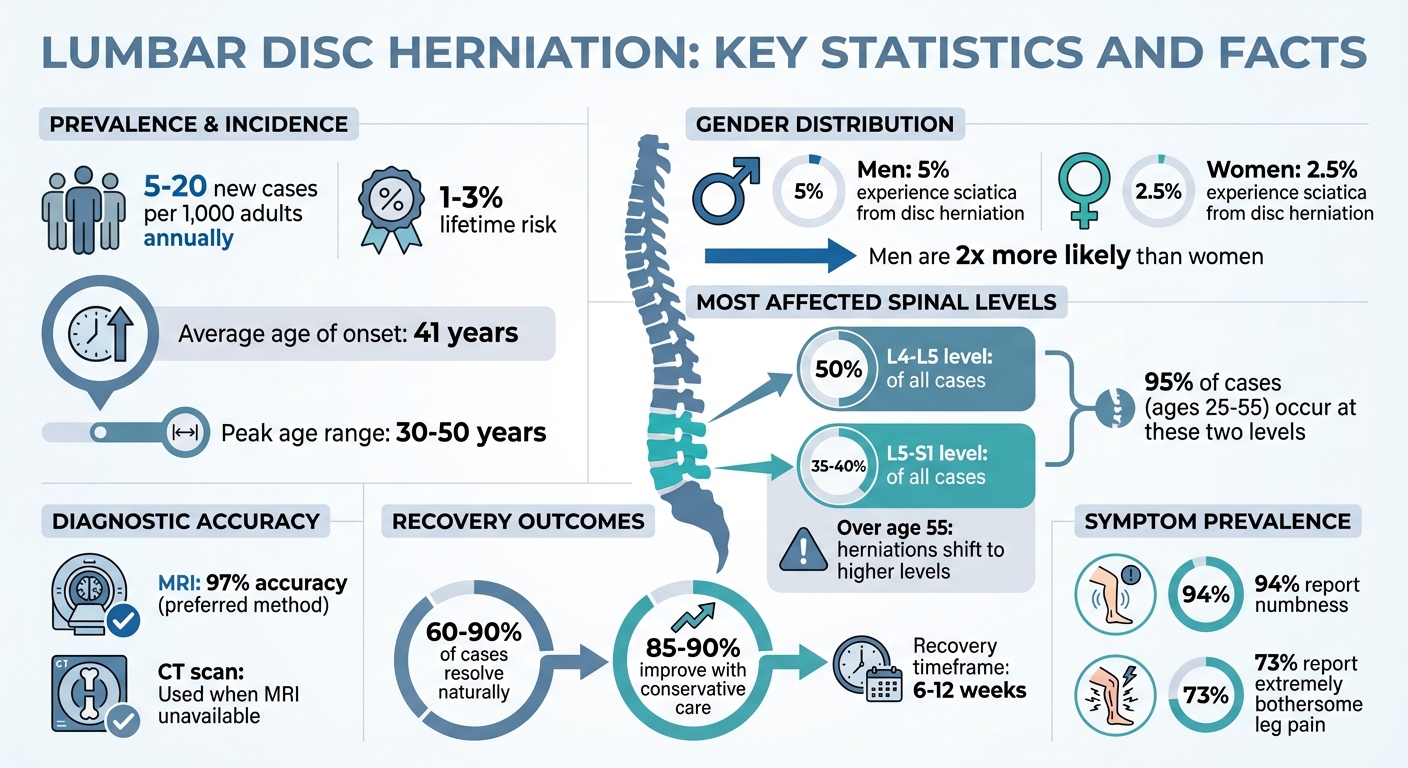

- Prevalence: 5–20 new cases per 1,000 adults annually; lifetime risk of 1–3%.

- Risk Factors: Age, heavy lifting, smoking, high BMI, and genetics.

- Diagnosis: Pain history, physical exams (e.g., straight leg raise test), and MRI for confirmation.

- Treatment: Conservative care (NSAIDs, physical therapy) is effective for most cases. Surgery is reserved for severe or persistent symptoms.

MRI is the preferred imaging method, with 97% accuracy, while CT scans are used when MRI isn’t feasible. Routine imaging is discouraged unless red flags like neurological deficits or suspected serious conditions are present.

WFNS Recommendations:

- Focus on non-surgical care first.

- Reserve imaging for symptoms lasting over 6–12 weeks or serious neurological issues.

- Address red flags, such as cauda equina syndrome, immediately.

Most patients recover without surgery, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate care.

Lumbar Disc Herniation Statistics: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Recovery Rates

Who Gets Lumbar Disc Herniation

Age, Gender, and Incidence Rates

Lumbar disc herniation tends to impact adults between the ages of 30 and 50, with the average onset occurring around 41 years old [6]. Men are twice as likely to develop this condition compared to women, with about 5% of men and 2.5% of women experiencing sciatica caused by disc protrusion [7].

The likelihood of herniation increases with age due to disc degeneration. This process involves a decline in proteoglycan production and disc dehydration, which weakens the structure of the discs over time [6]. These age and gender patterns provide a foundation for understanding where herniations most often occur in the spine.

Most Affected Spinal Levels

When it comes to specific spinal levels, the lower lumbar spine is the most common site for herniations. Around 50% of cases occur at the L4–L5 level, while 35–40% are found at L5–S1 [1]. For adults aged 25 to 55, nearly 95% of symptomatic herniations are located between these two levels. However, in individuals over 55, herniations are more likely to develop at levels higher than L4–L5 [7].

Risk Factors

Several factors, both internal and external, can increase the risk of lumbar disc herniation. Certain jobs that involve heavy lifting, frequent bending, or exposure to whole-body vibration put added strain on the lumbar spine [5][6].

Lifestyle choices also play a role. Smoking, a high BMI, and prolonged inactivity place additional stress on the discs. For women, cardiovascular health issues may further contribute to the risk [6].

Genetics can’t be overlooked either. Research has identified specific genes – linked to collagen, aggrecan, vitamin D receptors, and matrix metalloproteinases – that influence disc degeneration [7]. If lumbar disc herniation runs in your family, you may face a higher risk, even without other contributing factors.

Clinical Diagnosis Methods

Patient History and Symptoms

Gathering a detailed pain history is a critical first step in diagnosing lumbar disc herniation. This process helps distinguish radicular pain, commonly known as sciatica, by examining its intensity, onset, and location [4].

"Pain history is the most important part of clinical evaluation. It should include questions on intensity, onset and localization." – WFNS Spine Committee [4]

Certain activities, like sitting, coughing, sneezing, or straining, tend to increase intradiscal pressure, intensifying symptoms. Patients often report worsening pain when bending forward but note relief when lying down [4][9]. Many describe a combination of sensations – numbness is reported by 94% of patients, and 73% find their leg pain extremely bothersome [8].

During the initial evaluation, clinicians also look for red flags. These include symptoms like saddle anesthesia, bladder or bowel dysfunction, and any history of cancer or infection [1][9].

Physical Examination Tests

After reviewing the patient’s history, a physical exam helps pinpoint specific nerve involvement.

One of the most commonly used tests is the supine straight leg raise (SLR). In this test, the examiner slowly lifts the affected leg while the patient lies flat. If pain and tingling occur below 45° and radiate past the knee – a positive Lasegue sign – it strongly supports the diagnosis [1]. Another variation, the crossed straight leg raise, involves raising the unaffected leg; if this action causes pain in the symptomatic leg, it may suggest a more central herniation.

The Hancock rule further aids diagnosis by requiring three out of four criteria: dermatomal pain, sensory deficits, reflex abnormalities, and motor weakness [1].

"A clinical diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy, could be made with a straight leg raise screening test, if also Hancock rule requirement is met." – StatPearls [1]

Muscle strength is evaluated using the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale, which ranges from 0 (no movement) to 5 (normal strength) [4]. Reflex testing is another key component; for instance, a diminished patellar reflex often points to L4 involvement, while a reduced Achilles reflex suggests S1 involvement [1].

Warning Signs Requiring Immediate Care

Certain warning signs demand urgent medical attention. Cauda equina syndrome, a surgical emergency caused by severe nerve root compression, presents with symptoms like saddle anesthesia, urinary retention, bowel or bladder incontinence, and sometimes bilateral leg weakness [9][1]. In such cases, immediate imaging and surgery within 24 hours are recommended to improve outcomes [4].

Other serious red flags include severe or rapidly worsening motor weakness, such as foot drop, as well as fever, unexplained weight loss, night sweats, or a history of cancer. Persistent, severe pain – especially in patients under 18 or over 50 – should prompt an immediate MRI and referral to a specialist [9][1].

How do you know if you have a lumbar Disc Herniation?

sbb-itb-ed556b0

Imaging and Radiologic Diagnosis

Once a clinical evaluation is complete, imaging plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis. It works hand-in-hand with clinical findings to ensure treatment is precise and effective.

MRI as the Preferred Imaging Method

MRI stands out as the most reliable tool for diagnosing lumbar disc herniation, boasting a diagnostic accuracy of 97% [1]. On MRI scans, herniated discs are typically identified by an increased T2-weighted signal in the posterior 10% of the disc [1]. Its ability to clearly visualize soft tissues – like discs, nerves, and the thecal sac – makes it superior to other imaging techniques.

In addition to detecting herniation, MRI can pinpoint various types of spinal stenosis, including central, lateral recess, and foraminal stenosis. It can also differentiate between causes of back pain, whether inflammatory, malignant, or infectious – areas where CT scans fall short. MRI’s consistency, thanks to its high inter-observer reliability, ensures dependable results [1]. Unlike CT myelography, MRI avoids radiation exposure and eliminates the need for invasive contrast injections [1].

When to Use CT Scans

CT scans become the go-to option when MRI isn’t possible. This might be the case for patients with pacemakers or older MRI-incompatible prostheses, such as certain hip or knee replacements [1][2]. CT scans are also helpful when MRI results are unclear or unavailable.

"CT scans are superior in showing bone, but not as useful as MRI in depicting soft-tissue pathologies, such as disc disease or spinal stenosis." – WFNS Spine Committee [9]

While CT scans excel at visualizing bony structures, fractures, tumors, and calcified discs, they fall short in showing nerve roots, making them less effective for diagnosing radiculopathy [1]. For patients unable to undergo MRI, CT myelography – though more invasive – remains an alternative [1][2]. These CT-based approaches are essential when MRI is not an option, helping clinicians make informed decisions about further imaging.

When Imaging Is Needed

Routine imaging for acute low back pain is generally unnecessary unless specific red flag symptoms are present [4][9]. For first-time cases without neurological deficits or warning signs, radiological evaluation is typically avoided.

"Imaging should not be a routine diagnostic tool, unless red flag signs are present." – WFNS Spine Committee [9]

If symptoms persist for 6 to 12 weeks without neurological deficits, an MRI may be recommended to confirm herniation [4]. However, immediate imaging is crucial in cases of severe or worsening neurological issues, persistent radiculopathy, or suspected conditions like cauda equina syndrome, malignancies, or infections [4][6][9]. Routine imaging for non-specific back pain often uncovers incidental findings, such as age-related degeneration, which may not explain the patient’s pain and could lead to unnecessary anxiety [9]. These guidelines help clinicians decide when imaging is truly necessary.

WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations

The WFNS Spine Committee offers practical guidelines for diagnosing and managing lumbar disc herniation (LDH), focusing on non-surgical options as the initial approach. However, they also outline specific scenarios where immediate action is necessary.

Diagnosis and Imaging Guidelines

Accurate diagnosis starts with a detailed evaluation of the patient’s pain history, including factors like intensity, onset, and location. Physical exams play a key role, assessing muscle strength, sensory changes, and sphincter function [4]. The WFNS guidelines highlight the importance of provocative tests, such as the supine straight leg raise, Lasegue, and crossed Lasegue signs, to confirm the diagnosis [4][3]. Disc-related pain often worsens with activities like bending forward, coughing, or performing the Valsalva maneuver, but tends to improve when lying down [4][9].

Routine imaging isn’t recommended for first-time acute low back pain unless red flags are present [9]. Imaging is typically reserved for symptoms persisting beyond 6–12 weeks or cases involving motor deficits [4]. Red flags that call for immediate imaging include age under 18 or over 50, recent trauma, fever, a history of cancer, or serious neurological symptoms like saddle anesthesia and urinary retention [9].

Timelines for Conservative Treatment

For most patients without severe neurological issues, conservative management is the preferred initial strategy [10][4].

"In the absence of cauda equina syndrome, motor, or other serious neurologic deficits, conservative treatment should be the first line of treatment for LDH." – WFNS Spine Committee [10]

The committee suggests a 6–12-week trial of conservative therapies before considering surgery, as the majority of acute radiculopathy cases – about 85% to 90% – resolve naturally during this period [11][12]. Treatment options include NSAIDs, acetaminophen, physical therapy with McKenzie exercises, and activity modifications. Bed rest is discouraged and should not exceed 48 hours [10][4]. For severe motor deficits (MRC grade ≤ 3/5), surgery within 3 days is recommended for optimal recovery, while cauda equina syndrome requires emergency decompression within 24 to 48 hours [11].

Chiropractic and Non-Surgical Interventions

The WFNS acknowledges that spinal manipulative therapy can provide short-term relief (up to 6 weeks) for acute low back pain, with results comparable to other standard treatments [4]. At Portland Chiropractic Group, evidence-based care includes spinal adjustments, McKenzie-inspired extension exercises, and manual therapies designed to reduce stress on lumbar discs [10].

Extension exercises are particularly helpful in easing pressure on affected nerve roots and promoting natural recovery. Combined with activity adjustments and ergonomic advice, these non-surgical methods support the body’s healing process during the critical 6- to 12-week window when most herniation cases resolve on their own [4][3].

Conclusion

An integrated clinical and imaging approach plays a key role in managing lumbar disc herniation effectively. Diagnosis hinges on a thorough clinical evaluation complemented by targeted imaging when necessary. Among imaging techniques, MRI stands out with an impressive 97% accuracy rate [1]. However, routine imaging isn’t recommended for first-time acute low back pain unless red flags are present. Typically, imaging is advised only after 6–12 weeks of persistent symptoms or when serious neurological deficits are observed [4].

The good news? Most patients see improvement within 6–12 weeks of conservative care [1]. In fact, 60–90% of symptomatic disc herniations resolve on their own, emphasizing the body’s natural ability to heal [4][3]. At Portland Chiropractic Group, we focus on evidence-driven methods like spinal adjustments, extension exercises, and tailored activity modifications to support recovery.

The key to successful outcomes lies in distinguishing between patients who need urgent intervention and those who can benefit from conservative care. Red flags – such as cauda equina syndrome or severe motor deficits – signal the need for immediate action, while the majority of cases respond well to non-invasive treatments [9][1]. For most individuals, conservative care grounded in evidence delivers outstanding results, with surgical or urgent interventions reserved for the most critical situations [9][1].

FAQs

What warning signs of lumbar disc herniation require urgent medical attention?

Certain signs of lumbar disc herniation require urgent medical attention. These include cauda equina syndrome, which may present as numbness in the groin, difficulty controlling bladder or bowel functions, or both. Other warning signs to watch for are quickly worsening muscle weakness, significant neurological issues, severe and unrelenting pain, fever or indications of a systemic infection, recent serious trauma, or unexplained weight loss.

If you notice any of these symptoms, it’s crucial to seek medical care immediately to avoid serious complications.

Why is an MRI typically used instead of a CT scan to diagnose lumbar disc herniation?

An MRI is frequently chosen to diagnose lumbar disc herniation because it offers highly detailed images of soft tissues. This allows doctors to clearly see the spinal cord, nerve roots, and disc material. Unlike CT scans, MRIs don’t rely on ionizing radiation, making them a safer choice for many patients. They’re also better at identifying smaller herniations that might go unnoticed with a CT scan.

This accuracy plays a key role in ensuring the right diagnosis, which is essential for creating an effective treatment plan.

What are the recommended non-surgical treatments for lumbar disc herniation?

Conservative treatment is often the first choice for managing lumbar disc herniation, as long as there are no serious neurological issues like cauda equina syndrome. The WFNS Spine Committee recommends starting with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to help ease pain and reduce inflammation. Patients are advised to adjust their daily activities, avoiding things like prolonged sitting, heavy lifting, or repetitive bending. As symptoms improve, they can slowly return to their usual routines.

Physical therapy is a crucial part of this approach, emphasizing core-strengthening exercises, flexion-based movements, and supervised stretching to improve stability and reduce nerve compression. For short-term pain relief, analgesics such as acetaminophen or muscle relaxants may be used. In some situations, a single epidural steroid injection can provide additional relief by reducing inflammation and aiding the recovery process. Surgery is only considered when symptoms fail to improve or worsen despite these conservative measures.

Related Blog Posts

- Why Is Fatty Infiltration in the Multifidi Muscle Important for a Chronic Low Back Pain Prognosis?

- Association between cervical MRI findings and patient-reported severity of headache in patients with persistent neck pain: a cross-sectional study

- Validating biomarkers of chronic whiplash-associated disorders through magnetic resonance imaging techniques

- Rethinking the disc: from degenerative narrative to adaptive potential

Comments are closed